Talking to Your Child About Mental Health

Mental health includes our emotional, psychological, and social well-being. It affects how we think, feel, and act. It also helps determine how we handle stress, relate to others and make choices. Mental health is important at every stage of life, from childhood and adolescence through adulthood. For more information click on the following link.

One would think that in the very informed and enlightened era in which we live today, there surely wouldn’t still be a stigma, prejudice and discrimination attached to mental illness. It saddens me, however, that there are some young people who feel ashamed to ask for support around their mental health. Generally, people are not ashamed to share with others when they are physically unwell, probably because getting sick is a part of being human and can happen to anyone.

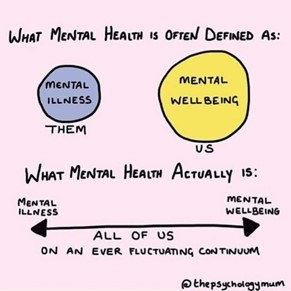

Mental illness, on the other hand, has been stigmatized for centuries, and even though most of us, thankfully, no longer view mental illness as demonic possession or label it as ‘crazy’, the ‘us versus them’ belief is still very much prevalent in our society today. Some still believe that it’s somehow shameful to struggle with one’s mental health and that it only happens to ‘them’ (for example, those coming from an unstable family home, those who have been diagnosed with a mental disorder, those who are weak, neurotic or are attention seeking, etc.). For this very reason, mental illness is often the best-kept secret in our society and people are often too ashamed to admit to others that they are struggling with anxiety, low mood, stress, grief, anger management or overwhelming emotions.

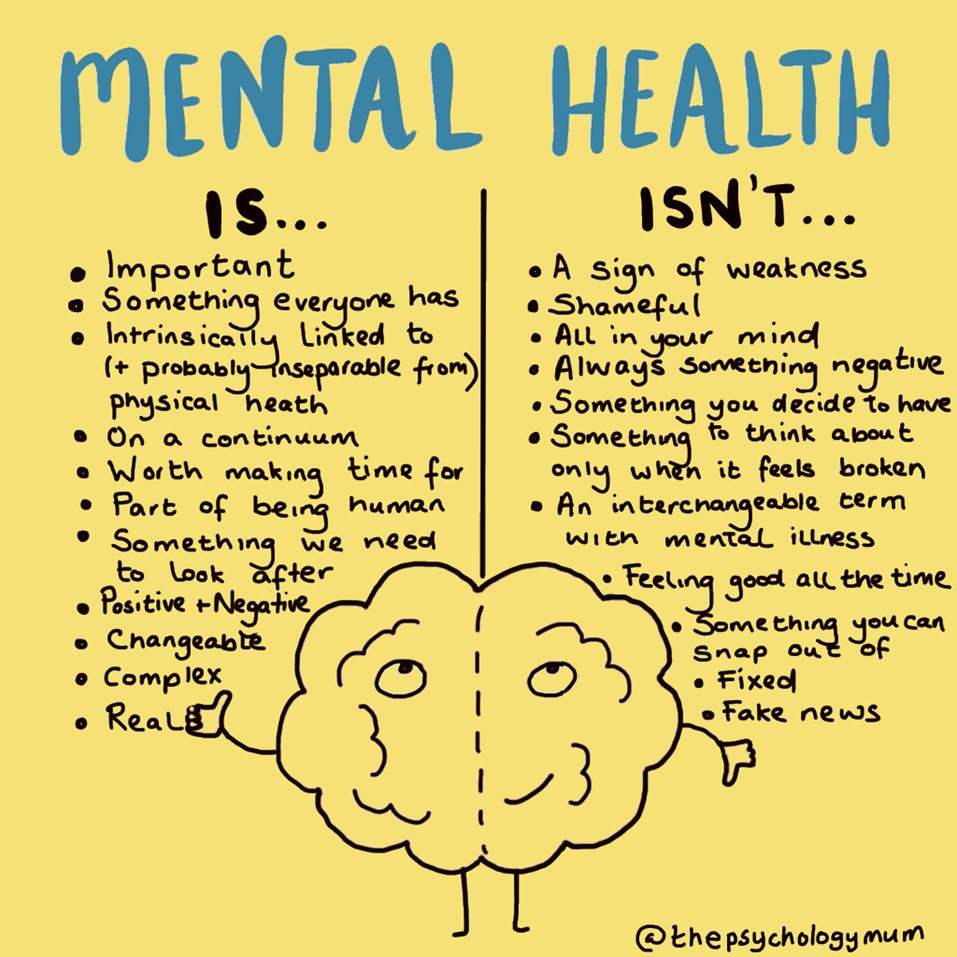

I absolutely LOVE this infographic by The Psychology Mum (Dr Emma Hepburn, who is a clinical psychologist, with expertise in neuropsychology, and blessed with an amazing talent in doodling and creating striking infographics on the important topic of mental health):

The truth of the matter is that just as every single one of us can become physically unwell, every single one of us can experience times when our mental health deteriorates, because we are all human and no one is above this. All of us can potentially be exposed to trauma, burnout, grief, bereavement, stress, divorce, financial hardship, retrenchment, addiction, emigration, bullying, chronic illness, pain, natural disasters, etc. which all have the capacity to negatively impact on our mental health. For this reason, I believe it is crucial for us to normalize the ever fluctuating continuum that all of us are on by talking about our own mental health more with others, including our children. Through this we can role model to them not the perfect, ideal version of ourselves whom they would struggle to live up to and relate to, but rather the brave enough person who can be vulnerable, and through this educate them on ways in which to purposefully and positively cope, for example through self-care, realistic self-talk, and self-compassion.

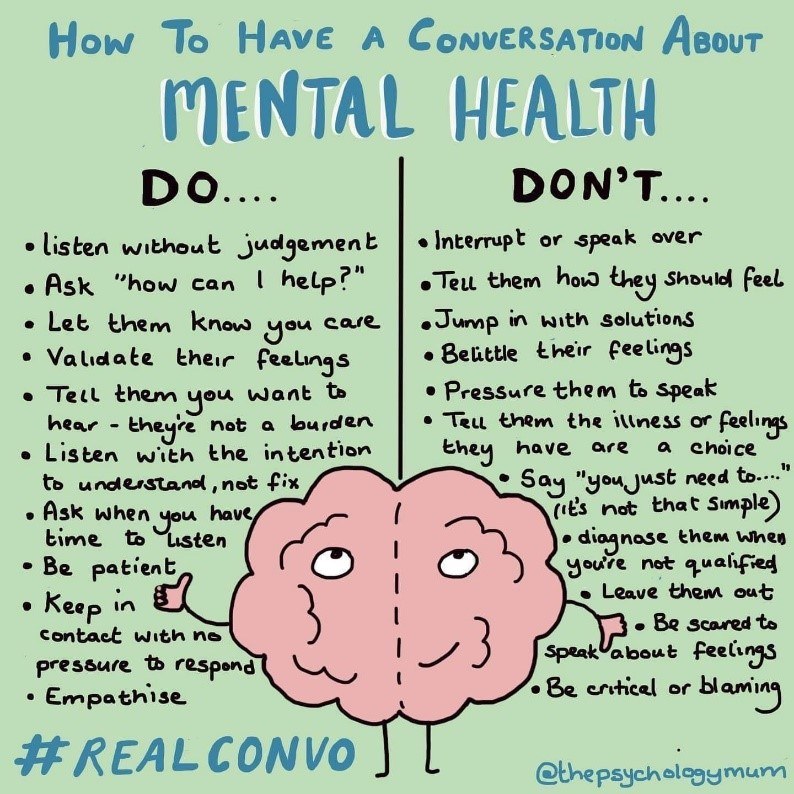

Mentalhealth.org provides the following tips on starting a conversation with your child about mental health:

Try leading with these questions. Make sure you actively listen to your child's response.

How to start a conversation with your child about mental health

- Can you tell me more about what is happening? How are you feeling?

- Have you had feelings like this in the past?

- Sometimes you need to talk to an adult about your feelings. I’m here to listen. How can I help you feel better?

- Do you feel like you want to talk to someone else about your problem?

- (If appropriate) I’m worried about your safety. Can you tell me if you have thoughts about harming yourself or others?

When talking about mental health problems with your child you should:

- Communicate in a straightforward manner

- Speak at a level that is appropriate to a child or adolescent’s age and development level (preschool children need fewer details than teenagers)

- Discuss the topic when your child feels safe and comfortable

- Watch for reactions during the discussion and slow down or back up if your child becomes confused or looks upset

- Listen openly and let your child tell you about his or her feelings and worries.

I’ll conclude with a few more infographics from The Psychology Mum.

Until next time,

Marisa Smit

Psychologist

1433

1433